This blog is intended to document the progress of developing and operating my HO scale model of the Burlington Northern Railway, for the purposes of orienting new operators and for my own record of its design process. The layout is located in Seattle, WA and models the area from Tukwila in the south, Bellingham in the north and Skykomish in the east. The time frame of the model is approximately 1973, three years after the merger that created the BN from the GN, NP, SP&S and CB&Q.

Wednesday, December 9, 2020

Wrestling with a BLI locomotive

Monday, November 16, 2020

The pros and cons of loose loads

The picture say it all - loose loads look great, until you accidentally knock a car off a cliff. Then you have a big mess to clean up. It will probably take me more time to clean up this mess than it would have taken me to make a simple balsa-wood insert for the car and glue some copper ore on top, years ago when putting the car in service. My train layouts are full of examples of "short cuts" that I took while constructing them, which I'm now paying for in unintended (or in this case, predictable) consequences.

Another issue with open loads is, if you put your finger(s) in them by accident, well, they look kind of weird. Here's an example, this time with a standard gage car in aggregate service:

Monday, November 2, 2020

Bayside Geeps

This is why I love modeling the BN in 1973 - all of these GP and SD locos in such a variety of paint schemes! Lately (thanks to encouragement and tutoring from friend Tim Taylor) I've been applying decals to re-number some of the models from their legacy road number to appropriate BN numbers, as was done after the merger in 1970 but before they were re-painted in BN green. It will take a while to get them all done, but the photo above is a sample of them that appeared parked one day at the "Bayside turntable". Of course, on the prototype BN the turntable was at Everett's Delta Yard, not at Bayside, but sometimes in model railroading you just have to make compromises. Also, I need to finish the track and scenery near the turntable. All in due time. The point is to just enjoy these stunning locomotives!

By the way, notice the clear depth of field in the photo. This photo is a composite of 6 photos I took with my iPhone, focusing each one on a different part of the scene, and then processing all 6 photos together using a computer program called "Helicon Focus". I just learned about this recently, although it's been around for years, and it's really changing the way I take pictures on the railroad now.

The SD9 in the foreground - notice its coupler. This is a "long shank" version of the "scale head" Kadee coupler, and the long shank is needed to keep the pilot from fouling the uncoupling pins of any cars that it might try to hitch to. The alternative is to cut the uncoupling pins off all your cars. I decided to use the longer coupler instead, despite its slightly strange appearance.

Finally, I apologize for the brick building held together by a rubber band. I've been busy laying track for the past 25 years and just haven't gotten around to finishing up some of the buildings that are needed in some of the scenes. In this case, the brick building will be replaced with a version of the "Scott Paper Co." paper mill in Everett, so it will eventually look quite different, and hopefully more realistic than it does currently. You can see the MILW and SP&S wood chip cars there, in the process of being unloaded. No bad smells, though, so far - I don't plan to model those.

Saturday, October 17, 2020

the new Athearn Genesis F7's arrive

The best thing about modeling the 1973 era on the Burlington Northern is that it took them about seven years to repaint all the legacy locomotives into the BN Green paint scheme. This means that my locomotive roster is a rainbow of colors with interesting histories. In this case, Athearn recently released the F7's in the original NP diesel paint scheme lettered for #6015A and 6015B. All I did was to remove that lettering and the front NP herald on the A unit (using MicroSet and a sharpened toothpick) and apply Microscale decals to the sides and number boards per prototype photos. The most time-consuming part of the project was researching which locomotive numbers would be seen in the Seattle area in 1973, and hadn't been repainted to BN green yet. I ended up deciding on FA#720 and FB#753, which were both based in Auburn, WA and were repainted later than 1973.

The final part of the project was to apply pan pastel weathering to bring out the detail, and to adjust decoder settings to get the performance from the locos that match my existing fleet. This includes setting the maximum speed to 30 miles per hour and mapping the brake function to F9.

The photo above shows the units parked on the mainline in Bayside Yard in Everett, WA, waiting for their first assignment.

Friday, September 18, 2020

The profound difference between a Timetable and an Operating Plan

Monday, September 14, 2020

More thoughts on car cards, switchlists, and computer-based car forwarding

Here's a summary of my current thinking about freight car routing on model railroads, in case it’s useful:

Monday, August 31, 2020

How to avoid building a basement layout altogether

I recommend watching the YouTube video George Sinos' presentation to the OPSIG which he gave yesterday. The link to it is here. The short story is, he built a switching layout in N scale on a shelf in the family room that ended up about 11 feet long, and it is so fun to operate, taking 2 people about an hour, that he's seriously considering canceling his plans to build a large basement layout downstairs. Here is what his track plan looks like:

He has a collection of about 400 freight cars that he rotates on and off the layout between groups of four op sessions, and uses a 4:1 fast clock, so that in four op sessions he covers about 16 hours of switching jobs to the various factories on the layout. He uses two ProtoThrottles for realistic engine control and JMRI PanelPro for a touchscreen to control the turnouts. I won't go on - you can watch the video for yourself.

His presentation reminds me of something I've often said to visitors to my layout - after 20 years of effort building the mainline from Seattle to Bellingham, I finally got around to building the Burlington, WA yard, and found it so fun to operate that I wondered why I didn't just start with that and not build the previous 20 year's worth of layout! I say it as a joke, but every joke has some truth to it.

Monday, August 24, 2020

Victoria BC in N with colored and numbered dots

Never one to miss an opportunity to add complexity where none is needed, I tried dividing the three N scale industry tracks described in my previous post into two or three industry spots, and then put small numbers inside the colored dots. Then I set up the spots as separate "tracks" in JMRI ops, and added them in a "pool" for each track. Now, instead of getting a switchlist from JMRI ops with four different destinations for cars, there are now eight. Without making any changes to the track!

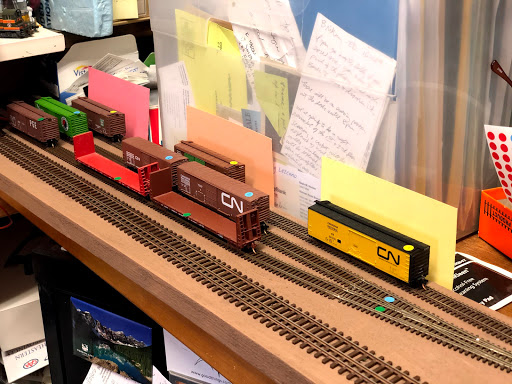

The diagram above shows the new named spots on each track, with the spot number in parentheses, and the dot colors for each track. I'm trying to represent downtown Victoria BC, based on an article in Layout Design Journal #62 (3rd Quarter 2018) by Cal Sexmith, so I picked industry names from the article and placed them on the three tracks in a quasi-logical order based on the order they might have been switched in real life. Then I placed colored 3x5 cards next to the track where the buildings might be, just to define the locations of the spots for now.

This photo shows the cars resting in their correct spots after the first (20 minute) operating session using the new scheme. It's amazing to me how fun it is to switch a small simple layout like this. I don't like the clunky layout of the JMRI ops switchlist, and haven't figured out how to improve it, so I spend a few minutes reading the switchlist and putting corresponding colored (and now numbered) dots on the cars. This is similar to a yard crew putting chalk marks on the side of cars. Then, I grab the throttle and enjoy about 20 minutes of switching fun.

The total investment in this particular N scale train layout so far: 30 min to paint the board, 30 minutes to prepare the switches and flextrack, 30 minutes to glue the track down to the board and connect wires to the NCE PowerCab, and 90 minutes to enter the track and cars into JMRI ops. - 3 hours total. $150 for the NCE DCC PowerCab, $50 for track, $300 for cars and locomotive - $500 total.

Sure, there's no backdrop, scenery or buildings, the rolling stock and track aren't weathered, etc. But the operation itself, switching cars around, is already very satisfying. That's all I'm sayin'.

Thursday, August 20, 2020

using colored dot (car tabs) to improve JMRI ops

If you've been struggling with using JMRI ops switchlists, try using color-coded stick-on "dots" stuck to the car tops to help you keep track of which car is supposed to end up on which track. It's not exactly prototypical to switch colored dots around, but it does make the whole thing easier and more fun. I've been experimenting with a Lance Mindheim style of "two turnout" switching layout, and the colored dots have really improved my enjoyment (and efficiency) of the switching moves.

I found out from Cal Sexsmith's article in the LDSIG Journal last year that Victoria had some interesting switching areas, and several car barge services to Seattle. So I decided to try doing some switching in Victoria. I put two turnouts on a plank (previously used only as a test track) with 5 pieces of N scale flex track and hooked it up to my NCE PowerCab and voila! Victoria!

Obviously the scenery leaves much to be desired, but it wasn't too hard to add these four tracks into JMRI ops, so I started generating switchlists and trying to use them. The switching was very tedious. Some of the cars needed to be moved, and some didn't. Some were moving offline, and some were moving between spurs. It was hard to remember what I was doing from one move to the next, and the N scale reporting marks are very small and it was hard to read them over and over again while constantly consulting the switchlist. The switchlist itself was formatted in a way that made it hard to keep track of the moves on. (I need to look into switchlist formatting options). Then I remembered I had seen a local N scale modular club using small colored dots as car tabs, so I pulled some out and tried using them to keep track of which cars were supposed to go where, according to the switchlist. It worked well! I could go through the switchlist only once, reading the reporting marks on each car and matching it to the switchlist, and placing the corresponding car tab on top of the car. That done, the actual switching was relatively easy, and fun! I've heard that some people "don't like switching colored dots around", but I'm wondering how different it is from switching cars based on chalk marks on the side of the car, like many prototype railroads would have used for switching. (Before computers, at least).

This operation, with only two turnouts and ten cars, is much more fun to operate than I was expecting! It takes me about 20 minutes to complete the work, long enough to make for an enjoyable break from routine daily activities without requiring a major time commitment. And if I want to make it more "meaningful," I could always generate a ferry run to Seattle and hand carry some of the cars back and forth to the main N scale layout. The only problem I see is that it is completely distracting me from all the other aspects of model railroading that I had been thinking were more important. Oh, well!

Monday, August 17, 2020

Progress towards remote ops

Above is a screen shot of a Zoom meeting set up with six live video views of the layout, suggesting that we are moving closer to being able to try doing a remote op session. I feel like I know just enough about all this to be dangerous, but not enough to make good decisions. Also, I keep thinking that if I can pull off a remote ops session in HO, so can you! :)

Wednesday, August 12, 2020

a master plan for holding virtual op sessions

Wednesday, August 5, 2020

Yard switching times vs. mainline running times

Monday, July 27, 2020

Forms for "off-spot" vs. "constructive placement"

Thursday, July 16, 2020

Helicon Focus at last!

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

Which do you prefer - Switchlists or Waybills?

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Setting up the ESU-V decoders in the new Atlas RS-3's

Thursday, June 25, 2020

renumbering a new Atlas BN RS-3

Thursday, June 18, 2020

onboarding the new Atlas HO RS-3's

This week, I "onboarded" two Atlas HO Alco RS-3 locomotives in BN paint. They are good looking and running additions to the roster for my layout's 1973-ish era. You can see them here in action on YouTube. The onboarding process for a "ready to run" locomotive involves these steps:

- Carefully taking it out of the box, which in this case involves unscrewing it from the bottom and replacing the screw holes under the loco fuel tank with special plugs provided in a plastic bag within the box. (which need to be cut from the sprue using an xacto knife or flush-cutting pliers) (5 min)

- Placing it on the track and seeing if, and how, it works. Sounds, lights, movement. (5 min)

- Put some alcohol (iso or eth) on a paper towel, and clean the wheels by running it at full speed while holding one of the trucks on top of the wet paper towel on the rails. This also confirms that both trucks are picking up power, which you want to know. (5 min)

- Run it at full throttle for about ten minutes in each direction, to "set the gears" (break it in). (20 min)

- (optional) Clean the wheels again, now that you've picked up whatever dirt was on the mainline track since you ran trains last. (3 min)

- Placing it in a cradle and replacing the couplers with KD #58 "scale head, center set, medium shank, whisker" couplers. (15 min)

- Putting it back on the track and checking if the coupler height is ok, and if the trip pin needs to be bent. (2 min)

- Opening a jar of "light india ink wash" (india ink diluted in lots of alcohol) and using a soft brush to cover the body and trucks with it. This somewhat dulls the sheen of new paint and brings out all the joints and details in the model, and dries quickly. (8 min)

- Taking it upstairs to my office and putting it on the test track, opening up the LokProgrammer app on my computer, and adjusting a variety of CV's in the LokSound ESU 5 decoder (which has 2000 user-adjustable CV's - don't get me started on that topic!) (10-60 min)

- Taking it back downstairs and testing to see if it still works ok. It may not, which may involve several more trips up and down stairs to get everything adjusted right. If I'm doing a lot of locomotives at one time I'll take the computer and test track downstairs to make the iterations easier. But climbing stairs is good exercise, too. (0-60 min)

- Getting out the pan pastels and dusting it all up with some off-white to bring out the handrails and truck side frames, followed by some rust applied to the couplers, truck springs, exhaust stacks and radiator and fan grilles. I try to do this weathering before the final speed-matching step, to make sure that I resolve any electrical pickup issues that all that chalk flying around might cause. (10 min)

- Getting out the speedometer and putting the loco back on the track. Setting the max and mid speed CV's 5 and 6 to give the same speed performance as your other locos. In my case, I'm using a top speed of 30 mph and a mid speed of 15 mph, which on these locos equates to CV5=88 and CV6=44. (It's good to do this later in the process, because you need to break the loco in at the higher speeds that it runs at, right out of the box.) (15 min)

- Getting out a different locomotive, and seeing if the braking rates match. They usually do, if you set them consistently, but in this case I found I had to increase the "brake 1" braking rate to CV179=200 in order to be consistent with my other locos. Most of my other locos are older SoundTraxx and LokSound decoders, so I'm still getting used to the new settings on the ESU 5. (5-30 min)

- Writing out a new "loco card" for each new loco you are onboarding. I usually put the manufacturer of the loco and the decoder on the back side in ink, and then some of the main CV values in pencil, so I can adjust them later on the fly if needed. (3 min)

- Going back upstairs and firing up my "Waybills" (Shenware Software) program on my Mac (using a PC emulator program called "Parallels", which I also used to run the PC-only LokProgrammer software) and printing out a "DCC functions" card to insert into the loco card. This tells an operator what will happen when they push each of the function buttons on the throttles. Since different decoders and locos (and layout owners) have different functions, this is necessary. In my case, I use F9 for brakes and F7 for dimming. (10 min)

- Going downstairs, inserting the DCC functions card in the loco card, and placing the loco card in the waybill box associated with the track that the loco is sitting on. We are now ready to run trains.

- In my era these locos should have yellow rotating beacons operating on top of their cabs. This would involve taking the shell off, finding the correct size yellow LED, soldering the correct resistor to one of the leads, drilling the correct size hole in the correct place, using the correct glue to put it at the correct height, adding some leads to the LED, soldering those leads to the correct pad on the decoder (if there is one!), programming the decoder to flash the rotating beacon at the correct rate, testing it, putting the shell back on, and testing it again. What am I waiting for? (60-120 min)

- You can see from the first picture above that the finish is still too shiny. Fixing this involves spray painting with a flat finish, which involves masking the windows. In future years I look forward to having the discipline to include this key step in my normal onboarding process. (30-60 min)

- Painting the wheels a rusty steel color. This involves either removing the truck side frames or applying paint in from the side while the loco is running. (20 min)

- Crew. There could be an engineer in the cab and a brakeman on one of the pilot decks. I do this as much as I can on switch engines, but it would look good on these locos too. Pre-painted figures wouldn't take long, but you could also custom-build people in certain poses and clothing and skin colors. (5-60 min)

- More weathering. Various vents, oil drippings, white fading below the lettering, rust spots on the fuel tank and elsewhere, wheel splash markings on both ends, etc. (30-60 min)

- Research and detailing. It would be fun to find pictures of these specific locomotives and to see what details are missing from the model that could be added. For example, BN 4082 was originally a Northern Pacific unit set up to run short hood forward, so the white reflector stripes should be on the opposite end. (10-200 min)

Thursday, June 11, 2020

switching large vs. small customers

I just had a long and illuminating conversation with Joe Green about his operating scheme for the large plants on his layout, and learned so much from him that I had to write a post about it. The photo above, which shows (out of focus) the three tracks representing the Scott Paper Co (just above the Roadway trailer) on my HO layout, will be referred to as we move through the subject. The main ideas are: (1) "constructively placed" vs. "off-spot" cars, (2) "open-gate" vs. "closed-gate" customers, (3) car orders vs. waybills, (4) the (sometimes conflicting) purposes of yards, and (5) ways to apply all this to a layout's operating plan (or, how to compromise between prototype and model practices so everyone has fun). I am no expert on any of this - these are just musings from a conversation between two model railroaders striving for "continuous improvement."

(1) Constructively placed vs. off-spot: If a railroad owns a car, it wants to use it as many times per year as possible, to generate a return on its investment. If a shipper has an inbound or outbound commodity, it wants to minimize the carrying costs associated with it. "Demurrage charges" developed so that railroads could charge shippers a fee for the use of a delivered car as a storage container, beyond a certain reasonable amount of free time (grace period) for loading or unloading it. This is fine if you have a small factory with a loading dock - the clock starts running on your grace period the moment the car is spotted at your loading dock. If for some reason the crew is unable to spot the car where you can get at it, it hasn't arrived yet, for your purposes, and is considered "off-spot," if it is on a nearby track but you don't have access to it yet.

But what about a situation where you are a larger factory, and you absolutely must have a certain number of cars per day shipped in and out in order to maintain full production, which is vital to your profitability? Are you willing to pay demurrage fees on cars that remain on nearby tracks (or yards) staged and waiting for your factory's "just-in-time" need? If the answer is yes, then those nearby cars would be considered "constructively placed", and the clock starts ticking on your grace period and demurrage charges. When the factory calls the railroad and says "we're ready for that car, bring it in (or take it out)!" the switcher gets over there (within a negotiated period of time) and spots it at the right spot.

So, in summary, it seems that the costs of holding an "off-spot" car belong to the (a) railroad, whereas the costs of holding a "constructively placed" car belong to the shipper/receiver (consignee, but don't get me started on all those other confusing terms and issues about who is paying the shipping charges).

(2) Open-gate vs. closed-gate customers: As I understand it, these terms are (CSX) railroad shorthand for some of the long-winded discussion above. For an open-gate customer, as soon as you deliver a car to their factory, you are done and the clock starts ticking on demurrage charges. If you park it at the wrong door, or on the wrong track, you made a mistake and it is "off-spot". If you can't get it to the right spot, because the track is full (or some other reason), you park the car somewhere nearby and hope you can get it in there tomorrow. It is still "in transit" and the clock hasn't started on demurrage charges, even though the car is right across the street from the intended receiver. For a closed-gate customer, a car being held nearby is "constructively placed" anywhere it is handy enough to be delivered to the factory as soon as the railroad gets the call that it's needed. The factory is willingly paying the demurrage charges in return for the assurance that it has what it needs "almost" on hand.

But Joe points out that there are really two "railroads" involved here - the one doing the delivering and the one owning the car. The latter is receiving the demurrage charges, and the former, well that probably depends on the specific agreement between the railroad and the customer. I just don't know enough about all this yet, clearly.

(3) Car orders vs. waybills: You can probably see where this is going. For a closed-gate customer, you can't deliver a car to the factory until they ask for it (I'm calling that a car order, but maybe they would just call it a phone call). If you have cars in the local yard with waybills billed to that factory, you have to hold them in the yard until instructed to deliver them. Once they have arrived in your yard, they are "constructively placed" and you have no choice but to store them (but at least you are making money off them). For an open-gate customer, if the waybill says take it there, you take it there ASAP, and if you have to park it nearby, it is "off-spot" and you will keep trying to deliver it every chance you get.

(4) The conflicting purposes of yards: On the prototype, some yards are meant to break down, classify, and build trains as they come and go. Other yards are meant to support nearby industries, serving both to help the local switchers sort cars and as a place to store cars which are either constructively placed or off-spot. But in model railroad situations, things are rarely that clear-cut. We end up with yards that are doing some of both. We surround our main yards with industries. And we never have enough track, especially not for storing extra cars that are not in motion.

(5) Ways to apply this to model operations: The popularity of model railroad operations is growing and evolving with each year and each modeler that gets involved. In my case, I started out thinking that if I had a car card with a waybill saying take this car to that factory, it was straightforward: (1) put the car in a train going the right direction, (2) take it out of the train at the nearest yard and give it to a switcher to deliver to the customer, and (3) deliver the thing to the customer, placing the car card/waybill in the corresponding box for that track. Job well done (although it might take three (or more) operating sessions for it to finally get there). Same thing for the reverse situation. And if there is no room for it at the customer's track, park it somewhere nearby and call it "off-spot". Some layouts are handling this by having a divider in the waybill box for each track labeled "off-spot", so you can see right away which cars on that track are supposed to be there and which are just temporarily parked there. So far so good. But, what about larger industries, like paper mills?

Here's a specific example: In/near Everett's Bayside yard (shown at the top of this blog post) I have three tracks with a total capacity of about 12 cars representing the massive Scott Paper Co. factory on the waterfront there. One of the Bayside yardmaster's job during their shift is to pull all cars out of there, and replace them with whatever comes in billed to Scott Paper. Sometimes they are so busy they never get to it at all. Sometimes they pull everything right away, and nothing comes in, so at the end of the session the plant tracks are empty. And sometimes they stuff the plant to the gills and there are still 6 cars in the yard billed to Scott Paper with no place to put them (we now know these have been "constructively placed" in Bayside yard). In several of these scenarios the plant would have been forced to shut down (totally unacceptable customer service!) and in others the yard is plugged up and not functioning well:

It seems like what we need is some sort of instruction to the Bayside yardmaster saying that "whatever you do, make sure you deliver 5 loaded woodchip cars, 3 empty boxcars and 2 tank cars to the Scott Paper Co. by the end of the session. Store anything else that comes in for Scott on your spare tracks in the yard, for next time. This way, at the next session, the next yardmaster can deliver these "constructively placed" cars to Scott right away, clearing up his yard, and then hoping the rest dribbles in from incoming trains during the session. The same sort of thing could be done for other major shippers on the railroad, such as the planned Bethlehem Steel plant in West Seattle. Now we know we can call them "closed-gate" customers. The rest of the smaller shippers, we can keep just using waybills to deliver cars to them, setting the cars "off-spot" nearby as situations warrant.

I seem to remember operating sessions somewhere (was it Al Frasch's?) where, when you started working in a town, you would find specific instructions about how to switch a certain factory, right there in the waybill box. I'm used to the idea of a "train instruction card" and a "car card/waybill" to explain the work I'm supposed to be doing, but now we are talking about adding a "switching agreement card" in the car card box (or on the fascia) that would make it clear how a specific shipper is expecting me to meet their needs. I'm going to go back and review past issues of the OPSIG's magazine "The Dispatcher's Office" and see if this has already been written up, and I just wasn't ready to understand it yet.

Finally, there's the question of how many times in an operating session do you need to switch a particular customer. If the plant is big enough, we could do like Joe Green does with his pulp and paper mill, and have two operating shifts work the mill switcher job during a single operating session, to make sure the customer's needs are met, and the mill stays in operation 24/7. On my layout's paper mill, my three tracks aren't big enough to justify that. On his layout, it makes sense:

After all, in all the fun of operating a model railroad, you wouldn't want to be responsible for shutting down the regional production of airplanes, lumber, steel rebar, or toilet paper, now, would you?